Chickens come home to roost: Morley’s (Fast Foods) Ltd v Nanthakumar & Ors

A recent High Court decision concerning London chicken shops highlights the importance of robust and forward thinking settlement agreements.

Founded in 1985 and now with around 100 franchises and presence on various delivery apps, Morley’s chicken shop is ever-popular and has various trade marks protecting the Morley’s brand. It also has trade marks protecting one of its popular chicken burgers, the “TRIPLE M” or “TRIPLE-M” burger. Around 1998, a copy-cat clucked up the courage to launch a rival chicken shop: Mowley’s. It was set up by Mr Kunalingam Kunatheeswaran (KK). KK even secured a UK trade mark for this rival brand (see below) and a dispute followed when Morley’s brought an action to invalidate this trade mark.

The dispute ended with the parties entering into a settlement agreement in 2018. At the time, no doubt, the parties would have been happy to put the dispute to bed without escalation to lengthy and expensive litigation. Use of the Mowley’s sign would end and the UK trade mark would be surrendered. However, it was false economy. The settlement agreement opened the door to future problems.

Settlement agreement problems

The settlement agreement contained a term in which KK was permitted to use “Metro’s Fried Chicken” in the form of the settlement logo (see below). It also expressly permitted KK to register the settlement logo as a trade mark and to use the settlement logo on any packaging. These express terms created a trade mark licence from Morley’s to KK to use the settlement logo:

The settlement agreement contained the ambiguous wording that KK could use the settlement logo “and any reasonable modifications thereto”. This wording left Morley’s a hostage to fortune as to how KK would “reasonably modify” the settlement logo in future.

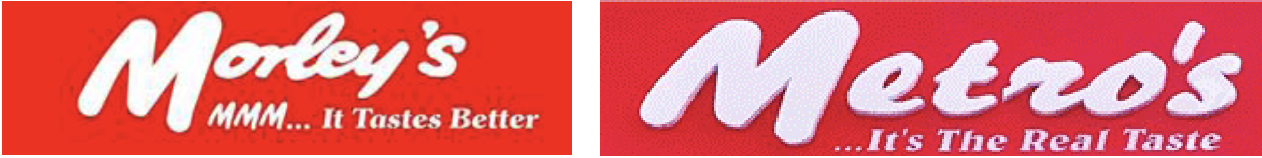

The decision to permit the use of the settlement logo failed to mitigate the chance of future contentious issues. The settlement logo was very similar to the Morley’s brand. There was the similar red colour background, similar use of a large “M”, and use of a similar cursive font. Maybe Morley’s was assuming that the use of the sign would be limited to shop signage and packaging, and that consumers would see the difference. However, it failed to consider the potential future growth of Metro’s and the proliferation of other similar chicken shops.

Another oversight was the failure to consider how the Morley’s brand and the settlement logo would be perceived in the online and digital environment. By the time of the settlement agreement, Deliveroo had been in the UK for five years and Uber Eats for two years. When viewed in the context of an app or website thumbnail, the Morley’s brand and the settlement logo were even more likely to be confused.

KK and its franchisees did not waste time launching Metro’s outlets. It quickly became apparent that those outlets were using signage with (un)reasonable modifications. The modified Metro’s logo looked incredibly similar to the Morley’s brand:

Social media quickly saw the similarities: “A fake Morleys called Metros. Wtf.”; “WHY TF IS THERE A MORLEYS KNOCK OFF MY BLIND ASS WANTED TO ORDER MORLEYS I FRICKING ORDERED METROS, WTF IS METROS??!”; “Genuinely how have morleys not sued metros for their logo lol”; “Did Morley’s rebrand as metros or something”; “Odd trend lately - Morley’s seem to be devolving into same-colour-new-name variants. Seen “Marley’s”, “Mawley’s”, “Maaley’s”, “Metro’s” etc”.

Chickens come home to roost at the IPEC

Morley’s took action against KK for use of the Metro’s logo and court proceedings in the English Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) followed. Whilst this appeared to be a straightforward trade mark infringement case, the chickens that came home to roost were the grant of the licence to KK and the “reasonable modifications” wording. In the IPEC, KK argued that the express grant of the licence permitted him to use the settlement logo with reasonable modifications, and the modifications made in order to create the Metro’s logo were reasonable. The IPEC judge rightly found that modifications that increased similarity with the Morley’s brand could not be reasonable, regardless of the licence granted. The Metro’s logo was found to be confusingly similar to the Morley’s brand and to infringe Morley’s trade mark rights under s. 10(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, with the similarities between the signs being the main focus, including:

- A medium degree of visual similarity between the Morley’s brand and the Metro’s logo (white lettering on a red background, the distinctive letter “M” as the first letter of the main word, and the similar font).

- Conceptual similarity, when considering the marks/sign as a whole, owing to the similar concepts portrayed by the straplines “It Tastes Better” on the Morley’s brand and “It’s the real taste” on the Metro’s logo.

The “MMM Burger”, a feature on the Metro’s menu, was also found to infringe Morley’s trade mark rights under s. 10(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994. The IPEC judge found that the “MMM Burger” had a medium-high degree of similarity with the Morley’s trade mark for “TRIPLE M”/“TRIPLE-M”. This was on the basis that the “MMM Burger” would have to be requested orally in store and that a substantial subset of consumers would request a “Triple M” burger (as opposed to ordering an “mmm” burger). And so, there was aural and conceptual similarity, although low visual similarity.

Creative arguments at the Court of Appeal

The problems already deep-fried into the settlement agreement provided KK and his franchisees the opportunity to deploy some creative points on appeal. The IPEC judge’s decisions on similarity were upheld by the Court of Appeal with relatively little fanfare. However, two arguments deployed by Morley’s are worth noting.

Morley’s argued that the licence granted to KK under the settlement agreement also constituted the grant of an implied sub-licence to the Metro’s franchisees. However, the settlement agreement contained numerous provisions excluding the rights of third parties (for example, the contract was unenforceable by third parties under the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 and the defined term “related parties” expressly excluding third parties). The settlement agreement also did not expressly grant any rights to sub-licence. Any licence granted to KK under the settlement agreement would not have extended to the franchisees. And, in any event, the Metro’s logo was not a “reasonable modification” of the settlement logo and so a sub-licence would not have covered use of the Metro’s logo by the franchisees in any event.

Another interesting point in the judgment related to the issue of the “drunken consumer”. The IPEC judge had found there to be two classes of average consumer for chicken shops:

- Children, young, people, students and families who make purchases from chicken shops at lunch, dinner and in the early evening. This group chooses by convenience of location, shopfront and potentially adverts on delivery websites. They will pay a low-medium degree of attention.

- Late-night and early-morning revellers who are likely tired, hungry and a significant subset of which will be intoxicated. This group chooses by convenience of location, shopfront and what is open late. They will pay a low degree of attention.

Various issues were raised about the validity of the second class of consumers, including that consumers that were intoxicated could not be “reasonably well informed or circumspect”, and so could not fall within the definition of the average consumer. The IPEC judge was, therefore, wrong to find a likelihood of confusion for the second class of consumers.

The Court of Appeal accepted that there should not be a second class of consumers. However, it gave a clear reminder that the purpose of the likelihood of confusion test is to assess how the average consumer would select the relevant goods and services and the level of attention they would pay. The IPEC judge may well have got it wrong by formulating the average consumer into two groups, and should have defined this group simply as a single class of consumers that go to chicken shops. However, this did not affect the IPEC judge’s final conclusion on likelihood of confusion. Both classes of consumer would choose their chicken shop by convenience of location and shopfront, and their levels of attention would overlap (that is, low or low-medium).

Ultimately, in the context of the whole likelihood of confusion test, the IPEC judge would have found infringement regardless of whether the average consumer had a low or low-medium degree of attention. The Court of Appeal confirmed that it would have come to the same conclusion.

Avoiding chicken-shop regret

The Morley’s-Metro’s dispute exemplifies how settlement agreements can be perilous, if not properly future-proofed.

It is important to remember that settlement agreements are not just backward-looking and concerned with shutting down prior disputes. They are also forward-looking, contractual arrangements that define the continuing relationship between parties within certain spaces.

Brands should carefully consider how they expect the marks in issue, and the market, to develop in the future. This can be very helpful to ensuring settlement terms are drafted to be sufficiently robust and to mitigate the possibilities of future disputes with a third party.

Case details at a glance

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: High Court

Parties: Morley’s (Fast Foods) Ltd v Nanthakumar & Ors

Citation: [2025] EWCA Civ 186

Date: 14 March 2025

Decision: dycip.com/2025-ewhc-civ-186