Protecting your after-market. Part 1: consumables

In many industries a manufacturer’s device serves to create a market for a consumable of that device, and often (for example, in the case of printers) this is the main source of profit, to the extent that the device itself may be sold as a loss-leader. Consequently it is desirable for the manufacturer to protect the consumables, in order to protect their after-sales market.

In some cases technological gatekeeping such as authentication codes or digital rights management can ensure the use of authorised consumables, or enable enhanced functionality when used; however these are often unpopular with end users and vulnerable to workarounds. Furthermore, there will be many cases where such technological approaches are not appropriate due to their cost or the use case of the consumable, or the functionality of the device. Consequently, more legally robust protections are desirable.

Where the consumable itself comprises an invention, the simplest solution is to patent it so that the consumable is independently protected. However this is not always possible, and so other options may need to be considered to avoid third-party supply and/or adversarial interoperability by competitors.

The design of the consumable may also be protected, although registered design protection typically excludes elements driven by a technical function or that are necessary to connect to another thing. This can reduce the ability of designs to protect consumables from compatible versions, although they are still very useful to protect design features associated with a brand, for example alongside trade marks.

Often however, an invention lies in how the main device uses a consumable, either in terms of efficiency, ease of use, speed, reliability or the like; but as a result the device only has the specific technical effect when operating as a system with the consumable in place. In this case, can the consumable be protected indirectly as part of the wider system?

In the case of Nestec v Dualit [2013] EWHC 923 (Pat), this issue was discussed at length.

Nestec v Dualit

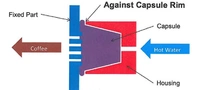

Nestec manufacture Nespresso coffee machines that make coffee from single-use capsules. The capsules have a lip so they can be clamped in a fixed manner within the machine, which allows water in one end of the capsule and coffee out the other:

Nestec originally had a patent for the capsule itself but in due course this expired. The patent at issue related to how more recent machines moved the used capsule into an extraction position for easy disposal, and claimed among other features an ”Extraction system comprising a device for the extraction of a capsule and a capsule that can be extracted in the device; the capsule comprising a guide edge in the form of a flange […]”.

The High Court discussed several issues relating to whether Dualit’s sale of compatible capsules was secondary infringement under section 60(2) of the UK Patents Act (UKPA).

The primary infringement Dualit would be enabling in this way is for the owner of the machine to “make” the claimed extraction system when combining the device and capsule. This system comprises the durable Nespresso machine and the perishable single-use capsules, which can be obtained independently of each other. Notably the relevant actions of the machine that characterise the invention are not altered by the presence or absence of the capsule (although clearly no coffee is produced and no capsule is extracted without one). As such the capsule appears entirely subsidiary to the machine. The judge also noted that “it is manifest” that the owner of the machine is not repeatedly making the same system each time they use their coffee machine.

Hence more generally where a consumable does not alter or enable a relevant function of a device (unlike when repairing a device), then it may not be said to make a composite system.

Separately, the judge also considered whether the act of making the claimed extraction system would be an infringing action at all, or was in fact performed by a “person entitled to work the invention”. Sale of a machine like the Nespresso results in the exhaustion of the patentee’s rights in respect of that individual product, and also confers an implied license on the purchaser to use the machine how they please. More pointedly the purpose of a Nespresso machine is to make coffee and so the purchaser can reasonably expect an implied licence to obtain and use coffee capsules with the machine.

Notably whilst the exhaustion doctrine will leave no patent right to be enforced anyway, an implied licence can be excluded by use of an explicit licence.

Hence in some cases, for example where the device and/or consumables are a specialist long term capital expenditure or leased (for example in the case of heavy plant machinery, assembly line equipment, or agritech machinery), sale of the device can include a contractual agreement to use a specific source for the consumable, even if only for a limited period (and subject to anti-competition provisions if applicable). This may be the best option where the consumable is not independently protected and is a wholly subsidiary element of the machine’s operation.

Whilst the Nestec case touched on whether a consumable constituted a part of a machine or not, this was a more central aspect to another case, Grimme v Scott [2009] EWHC 2691 (Pat).

Grimme v Scott

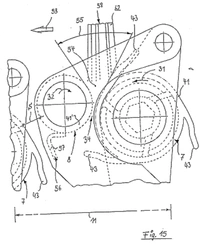

Here, Grimme’s patented invention was an agritech apparatus for separating potatoes from haulm, soil, and other impurities once dug up. It uses contra-rotating rollers comprising “an elastically deformable shell part”, where in each pair the upstream roller has ”extension parts (43) which extend beyond the cylindrical shell part and which are constructed as conveyor lips”.

Potatoes move over the rollers, and the lips push the potatoes forward whilst helping to knock and pull detritus down between the contra-rotating roller pairs.

Meanwhile, Mr Scott’s Evolution separator used steel rollers. In principle this meant that it did not infringe the patent with its elastically deformable rollers. However, it was considered clear that these steel rollers could be replaced with rubber ones, reducing the aggression with which the potatoes were handled and cleaned. It was also held that Mr Scott knew and designed his machine with this in mind, and that it was obvious that people would do this.

Hence in effect Mr Scott was supplying everything except an elastomeric version of the rollers, knowing that these would likely be added by end users. As such he was considered to be supplying means relating to an essential element of the invention.

In this case, rather than supplying compatible pods for an existing machine to create a patented system, in effect Mr Scott provided a compatible machine for existing pods – and in doing so stepped over the mark: “Mr Scott went further – in this case, replacing the rollers would be a one-off action that changed the ongoing operation of the device to match that of the patented system”.

Action points

The lessons from these cases are that, when developing a product used by a third-party device, or a device that uses third-party consumables, it is advisable to perform a freedom to operate check on whether and to what extent either element is protected by IP.

Similarly, when developing your own system using consumables, consider independent protection of each, and/or where possible an explicit licence for supply.

As a final point, replacing the steel rollers with rubber ones is not an act of repair, as the resulting machine operates differently (it does not restore the original state of the machine); how far the right to repair a patented device can go is the topic of the next article in this series.

Case details at a glance

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: High Court

Parties: ESTEC SA (claimants), NESTLÉ NESPRESSO SA, NESPRESSO UK LIMITED and DUALIT LIMITED (defendants), PRODUCT SOURCING (UK) LIMITED and LESLIE ALEXANDER GORT-BARTEN

Citation: [2013] EWHC 923 (Pat)

Date: 22 April 2013

Decision: dycip.com/2013-ewhc-923-pat

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: High Court

Parties: GRIMME LANDMASCHINENFABRIK GmbH (claimant), & Co. KG, and DEREK SCOTT (defendant) (T/A SCOTTS POTATO MACHINERY)

Citation: [2009] EWHC 2691 (Pat)

Date: 03 November 2009

Decision: dycip.com/2009-ewhc-2691-pat