Guide to the Unified Patent Court (UPC)

-

Introduction

-

Legal sources

-

Jurisdiction

-

The opt-out from the UPC

-

Transitional period

-

UPC structure

-

Where to start a case

-

Transfer of actions between divisions and miscellaneous rules on choice of forum

-

Bifurcation of infringement and revocation proceedings

-

Languages

-

Representation

-

Judges

-

Overview of proceedings

-

Stay of proceedings

-

Remedies and defences

-

UPC court fees and cost recovery

-

Relationship with opposition and appeal proceedings at the EPO

-

Claim interpretation

-

Added matter

-

Sufficiency

-

Novelty

-

Inventive step

View our UP & UPC webinars

We have published an ongoing series of UP & UPC related webinars providing UPC observations and analysis of the latest UPC decisions.

View webinarsThis guide was last updated on 30 September 2025.

Unified Patent Court services

Our expert team of European patent attorneys has a track record in contentious proceedings that is second-to-none, making us the ideal partner of choice for defending our client’s interests before the UPC. For more information, please visit the Unified Patent Court services page on this website.

Read moreIntroduction

The Unified Patent Court entered into force on 01 June 2023. Together with the European patent with unitary effect (unitary patent or UP), the UPC represents the biggest change in the European patent landscape in more than 40 years.

At its entry into force, the UPC was a new, international court for patent litigation in Europe for states which are both members of the European Patent Convention and member states of the UPC Agreement. It is a single court, comprising both first and second instances, with multiple locations.

It is the product of years of discussions and negotiations that were aimed at the objective of providing a single litigation forum for patent disputes in Europe. To that end, it has procedures and rules that are based on a combination of different European practices.

The UPC is the court for litigating European patents, whether or not as unitary patents, with effect broadly for member states of the European Union. This therefore necessarily excludes significant non-EU states like Switzerland, Turkey and Norway. Furthermore, although Spain and Poland are member states of the EU, they have not signed up to the UPC Agreement.

The UK, which was an original signatory of the UPC Agreement and indeed ratified the UPC in December 2016, withdrew its ratification of the UPC Agreement and from the UP. Therefore, although there is some harmonisation for litigating patents across Europe with the UPC, at present European litigation remains somewhat fractured without unitary harmonisation.

Specific guidance

It is impossible in a guide of this nature to deal with every detail of the UPC Agreement, the Rules of Procedure, the fees and cost rules, and the decisions and orders issued by the UPC Courts of First Instance and UPC Court of Appeal. If you are contemplating using the system, or finding yourself litigating before the UPC, we can provide you with specific and detailed advice relating to your particular circumstances. Nevertheless, we hope this guide provides a useful and helpful summary of the system, how it works and what the implications may be for you.

Legal sources

The UPC was established by the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (the UPC Agreement) which was signed on 19 February 2013 by 25 European countries.

In July 2020, following Brexit, the UK withdrew from the UPC Agreement, leaving the following 24 countries:

- Austria

- Belgium

- Bulgaria

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Ireland

- Italy

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Netherlands

- Portugal

- Romania

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Sweden

The UPC Agreement forms the bedrock of the legislation that governs the UPC. Article 24 of the UPC Agreement states that the UPC bases its decisions on:

- EU law (including the two European Union Regulations creating the UP);

- the UPC Agreement;

- the European Patent Convention (EPC);

- other international agreements applicable to patents and binding on all the participating member states (such as The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights or TRIPS); and

- national law.

The UPC Agreement is effective in all signatory countries that have ratified the UPC Agreement. References in this guide to “contracting member states” are therefore to countries that have both signed and ratified the UPC Agreement. Member states within this group will increase in number as more signatories ratify the Agreement. A map and list of current UPC member states is available on the Unified Patent Court’s website: https://dycip.com/upc-member-states.

In addition to governing law, there are several important sets of rules that apply in the UPC, including the Rules of Procedure and various Decisions of the UPC Administrative Committee.

Jurisdiction

Actions within the competence of the UPC

The UPC has competence for infringement actions, declarations of non-infringement, revocation actions, and related counterclaims concerning patents that fall within its jurisdiction. This includes all forms of relief and protective and/or preventative measures. The UPC also has competence to deal with claims arising from decisions of the European Patent Office (EPO) relating to its function as the granting and administrative body for UPs.

Regardless of the patent concerned, the UPC does not have competence for contractual disputes relating to patent licences or ownership – these remain the preserve of the national courts, and are governed by relevant national law.

Patents within the jurisdiction of the UPC

(a) European patent with unitary effect (unitary patent or UP)

UPs fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the UPC, for disputes within its competence. All infringement and invalidity actions, and counterclaims, involving UPs must therefore be brought before the UPC.

(b) Conventional European patents

Conventional European patents validated in contracting member states (‘relevant conventional European patents’), also fall within the jurisdiction of the UPC, although the extent to which they do so will change over time and in particular will alter at the end of the transitional period.

During the transitional period, relevant conventional European patents can be litigated in either the UPC or national courts.

In Mala Technologies Ltd v Nokia Technology GmbH (UPC_CoA_227/2024), the Court of Appeal emphasised that a UPC court should only decline jurisdiction if the proceedings involve the same cause of action and the same parties as parallel proceedings in a national court of a UPC member state, to avoid potential conflicting decisions. This applies even when such parallel national court proceedings have been brought before the start of the transitional period. Ultimately, the Court of Appeal decided that the UPC had jurisdiction to hear a revocation action, even though there were parallel invalidity proceedings before the German national court, because the parties involved in the UPC and German proceedings were not identical.

As confirmed in DexCom Inc v Abbott (Laboratories & Ors) (UPC_CFI_230/2023), a claimant may choose to exclude certain acts of infringement from an action in order to avoid the inconvenience of parallel proceedings between the UPC and national courts during the transitional period.

It is also possible during the transitional period to opt conventional European patents out of the jurisdiction of the UPC completely (see “The opt-out from the UPC” section below). At the end of the transitional period, any relevant conventional European patents that have not been opted out will fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the UPC.

(c) Long arm jurisdiction

The UPC also has what is referred to as “long arm jurisdiction” to hear actions concerning European patents validated in non-UPC contracting member states. The CJEU confirmed in BSH v Electrolux (C-399/22) that EU member state courts, including the UPC, have jurisdiction to make infringement decisions involving foreign patents and award remedies, including damages and a final injunction, against a defendant domiciled in an EU member state.

The Düsseldorf Local Division decided in FUJIFILM Corporation v Kodak Holding GmbH & Ors (UPC_CFI_355/2023) that the UPC has jurisdiction to hear infringement actions concerning the UK part of a European patent. Similarly, in Mul-T-Lock (France & Suisse) v IMC Créations (UPC_CFI_702/2024), the Paris Local Division decided the UPC was competent to hear an infringement action with respect to the Spanish, Swiss and UK parts of a European patent; and to provide a decision that only has inter partes effect on the validity of the UK part.

The opt-out from the UPC

Article 83 of the UPC Agreement provides that relevant conventional European patents can, before the end of the transitional period of the UPC, be opted out from the UPC’s jurisdiction. This may be desirable for holders of business-critical patents that they do not wish to place at risk of central revocation. Key aspects of the opt-out include:

- The opt-out only applies to relevant conventional European patents – it has nothing to do with unitary patents which must be litigated in the UPC. So if you choose a UP, you automatically choose to litigate that patent in the UPC. If an opt-out has been filed before requesting unitary effect, the request for unitary effect overrules the opt-out (see below).

- Any relevant conventional European patent can be opted out provided it has not already been litigated before the UPC. The Vienna Local Division confirmed in CUP&CINO v Aplina Coffee Systems (UPC_CFI_182/2023) that an action bought in the UPC (here an application for a preliminary injunction) meant that a subsequently filed opt-out was invalid.

- Subject to any later opt-out withdrawal (see below), once opted out, a relevant conventional European patent will be opted out of the UPC for its entire life – the opt-out itself will therefore last beyond the end of the transitional period.

- Published European patent applications can also be opted out but any that become a UP after grant will automatically fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the UPC.

- The opt-out can be exercised until one month before the end of the transitional period (see below).

- It is possible to withdraw an opt-out from the UPC but this can only be done once. It is not possible to opt back out again.

- Withdrawal of an opt-out will not be possible if the patent has been litigated before a national court during the transitional period. However, in AIM Sport Development v Supponor (UPC_CoA_489/2023 and UPC_CoA_500/2023), the Court of Appeal confirmed that opt-out withdrawals are not affected by national proceedings brought before a national court before the start of the transitional period (that is, in advance of 01 June 2023).

- All relevant conventional European patents in a “bundle” must be opted out together: it is not possible to split up different national validations of relevant conventional European patents and take different decisions regarding the opt-out.

- The opt-out can only be exercised by the true proprietor or applicant (see below). If there is more than one, all proprietors must agree. This was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Neo Wireless GmbH & Co KG v Toyota Motor Europe (UPC_CoA_79/2024). A declaration must be filed to confirm that the application is made by the person entitled to opt out, and on behalf of all relevant proprietors. If the declaration proves to be false or inaccurate, the opt-out will be invalid.

- Licensees cannot opt out.

- Where there are granted supplementary protection certificates (SPCs) in UPC states attached to a patent, the two rights must be opted out together. It is therefore not possible to opt out a granted SPC without the relevant patent, and vice versa.

- The proprietorship rules therefore mean that where a granted SPC and the relevant patent are in different ownership, all owners must agree to opt out.

- There is no official fee to opt out, or to withdraw the opt-out. Associated costs relate to administrative time and any professional costs involved in the provision of advice relating to the opt-out, and any opt-out service used.

Given the implications of any false or inaccurate declaration (see point 9 above), it is essential to check the proprietorship position in advance, and seek any consents that may be necessary. There will be an assumption that the proprietor or applicant on the relevant national or EPO registers is the entity or person entitled to opt out. It is the true proprietor or applicant who has the right to opt out, however, so this needs to be checked as it may not be the same person as entered on the register. It may be sensible to try to correct any registers that are out of date, subject to costs considerations. If the application to opt out is made in the wrong name, it will be ineffective. Corrections can be made but the opt-out will not be back dated, the opt-out will be effective from the correction date, which could cause problems.

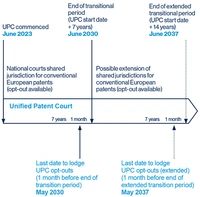

Transitional period

The UPC Agreement provides for the current transitional period during which the UPC shares jurisdiction with national courts for relevant conventional European patents.

The end of the transitional period also marks the end of the time during which applications to opt out can be made (in fact, as mentioned above, they must be lodged no later than one month before the end of the transitional period).

Article 83 of the UPC Agreement provides that the transitional period will last for seven years from the commencement of the UPC. This means the transitional period is expected to end on 01 June 2030.

However, the UPC Agreement also provides that there will be a consultation with users after five years of operation of the UPC, as a result of which the transitional period could be extended by up to a further seven years (so possibly up to 01 June 2037).

UPC structure

The UPC comprises first and second instance courts, together with a Registry and an Arbitration and Mediation Centre.

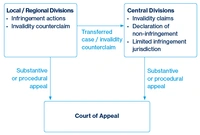

First Instance

The First Instance of the UPC is made up of Local, Regional and Central Divisions.

Local and Regional Divisions primarily have competence for infringement actions, with or without invalidity counterclaims. The Central Division primarily has competence for invalidity actions, with or without an infringement counterclaim. It also has competence for actions for a declaration of non-infringement.

Any contracting member state may host a Local Division. Many already do so, and indeed some are able to host more than one (for example, Germany hosts multiple Local Divisions). The number and locations of these may vary over time.

Some contracting member states have joined together to host a Regional Division rather than have their own individual Local Divisions. These function in essentially the same way as Local Divisions.

The Central Division has three branches, which were originally to be located in Paris; London; and Munich. The withdrawal of the UK meant the branch located in London was relocated to Milan. The Milan Local Division opened its doors on 01 June 2024.

Second Instance Court of Appeal

The UPC has a Court of Appeal, with a single location in Luxembourg.

Registry

The UPC has a central Registry, based in Paris, with sub-registries at each division. The Registry is responsible for the administration of all proceedings, including service of all documents (which should be filed at the Registry, not sent directly between the parties).

Mediation and Arbitration Centre

The UPC has a Mediation and Arbitration Centre, located in Lisbon and Ljubljana. This has its own rules and procedures. Parties have no duty to use alternative dispute resolution (ADR) although they will be encouraged to do so, whether using the UPC Mediation and Arbitration Centre, or any other independent service located in a number of contracting member states.

Where to start a case

Except where the parties have specifically agreed on a particular division for their case, the following sets out where various UPC actions should be brought.

Infringement actions

Actions for infringement should be brought before the Local or Regional Division in either:

- The contracting member state in which the infringement occurred; or

- The contracting member state where the defendant (or one of them, if multiple defendants) has its residence or principal place of business or, in the absence of either of these, its place of business.

An action for infringement can be brought in the Central Division where either:

- The defendant has its residence, principal place of business or, in the absence of either of these, its place of business outside the territory of the contracting member states; or

- The contracting member state concerned does not have a Local Division or participate in a Regional Division.

An action against multiple defendants can be brought only where the defendants have a “commercial relationship” and the case relates to the same infringement. Based on SVF Holdco v ICPillar LLC (UPC_CFI_495/2023), belonging to the same group of legal entities and having related commercial activities aimed at the same purpose (such as R&D, manufacturing, sale and distribution of the same products) are sufficient to be considered as “a commercial relationship”. Selection of a division may be justified by the residence/place of business of only one of several defendants, also based on SVF Holdco v ICPillar LLC (UPC_CFI_495/2023).

Counterclaims for revocation or a declaration of non-infringement must be brought before the same division as the infringement action to which they relate. However, this does not include standalone revocation actions filed by a separate legal entity, based on Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril Italy srl (UPC_CFI_255/2023).

The jurisdiction rules provide the potential for choice of UPC division in many infringement cases, in particular where there may be multi-country infringement and/or multi-defendant litigation.

Revocation actions and actions for a declaration of non-infringement

The Central Division has jurisdiction for actions for revocation or for a declaration of non-infringement. Such actions should be brought before the relevant branch of the Central Division, based on technology.

| Milan | Paris | Munich |

|---|---|---|

| (A) Human necessities without SPCs. | (B) Performing operations; transporting. | (C) Chemistry; metallurgy. |

| (D) Textiles; paper. | (F) Mechanical engineering; lighting; heating; weapons; blasting. | |

| (E) Fixed constructions. | ||

| (G) Physics. | ||

| (H) Electricity. | ||

| (A) and (C) SPCs. |

Transfer of actions between divisions and miscellaneous rules on choice of forum

Actions may be transferred or otherwise moved from one division to another, or brought in a division that is outside the principal rules, in a number of circumstances, including:

- Where the parties agree that an action may be brought before the division of their choice.

- Where a Local Division decides to transfer all or part of a case to the Central Division when a revocation counterclaim is brought in an infringement action.

- Where the parties agree to transfer.

- Where a revocation action is pending before the Central Division and an infringement claim is then brought before a Local or Regional Division (in which case, the defendant in that latter claim can choose to continue the action for revocation in the Central Division or commence a counterclaim in the Local or Regional Division).

- Where an action for a declaration of non-infringement is pending before the Central Division and an infringement action is then brought before a Local or Regional Division (in which case the action for a declaration will be stayed).

- Where more than one action is pending before different panels (whether in different divisions or not) concerning the same patent, the relevant panels of the UPC may agree that the two actions shall be heard together.

In scenario 4, timing of lodging an action can be critical to where a case is heard. In Amgen Inc v Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH & Ors (UPC_CFI_1/2023), both parties filed their actions on the same day. Sanofi filed its revocation action designating the Munich Central Division, and less than 20 minutes later Amgen filed its infringement action at the Munich Local Division. Because Sanofi’s revocation action was filed first, the case was heard at the Munich Central Division.

Bifurcation of infringement and revocation proceedings

The UPC is by default a non-bifurcated system. However, bifurcation of infringement and revocation proceedings can occur in two different scenarios:

- When a counterclaim for revocation is filed, in response to an infringement action brought at a Local or Regional Division, and the Local or Regional Division decides to refer the revocation counterclaim to a Central Division, but retain the infringement action.

- When a revocation action is filed at a Central Division and the patentee subsequently files a separate infringement action at a Local or Regional Division.

Bifurcation in scenario 1 has only been granted in specific circumstances, and Local or Regional Divisions have tended to rule on both infringement and validity in most cases. For example, in Plant-e (Knowledge BV & BV) v Arkyne SL (UPC_CFI_239/2023), the Local Division of the Hague stated that it was preferable for validity and infringement to be decided on the basis of a uniform interpretation of the patent by the same panel composed of the same judge.

However, when a stand-alone revocation action is already pending before a Central Division on the same patent, Local or Regional Divisions have been more willing to bifurcate. For example, in MED-EL Elektromedizinische Geräte Gesellschaft mbH v Advanced Bionics (AG & Ors) (UPC_CFI_410/2023), the Mannheim Local Division referred a revocation counterclaim to the Paris Central Division which was handling a parallel stand-alone revocation action, while retaining the infringement action.

In bifurcation scenario 2, a stay of the infringement proceedings may be issued to prevent bifurcation of proceedings. However, in Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril (Gmbh & Life Sciences Pvt Ltd) (UPC_CFI_15/2023), the Munich Local Division stated that there was no obligation to stay the proceedings as such, and refused to stay infringement proceedings, pending an appeal of the Paris Central Division’s finding on validity of the patent in question. The Munich Local Division subsequently found the patent to be infringed.

Languages

Local or Regional Divisions

The language of proceedings before the Local or Regional Divisions is:

- one or other of the official languages of the contracting member state hosting the division, or the official language designated by the contracting member states sharing a Regional Division; or

- to the extent designated by the relevant division, one or other of the official languages of the EPO (English, French or German).

Alternatively, in circumstances where the parties and panel agree, and/or where the panel of the relevant division believes it to be fair and convenient to do so taking into account the circumstances in particular of the defendant, the language of the patent may be used. This may be particularly important where defendants are sued in a division which uses an entirely unfamiliar language.

English is available before all divisions of the UPC, and is the predominantly used language at First Instance. However, care should be taken when selecting a language and a division, having regard to the likely impact of using what may be a second or even third language of the participants, judges and representatives.

Importantly, an application can be made for changing the language of proceedings to that in which the patent granted. In the majority of cases European patents are granted in English.

The Court of Appeal in Curio Bioscience Inc v 10x Genomics Inc (UPC_CoA_101/2024) emphasised that when deciding whether to allow such a language change, all relevant circumstances must be taken into account. These should primarily be related to the specific case and position of the parties, and the defendant’s position in particular is to be taken into account.

The importance of the defendant’s position was also clear in Arkyne Technologies SL v Plant-e (Knowledge BV & BV) (UPC_CFI_239/2023) and Aarke AB v SodaStream Industries Ltd (UPC_CFI_373/2023), ,where the Local Divisions of Düsseldorf and the Hague favoured SME defendants by granting a change of the language of proceedings to English.

Central Division

The language of proceedings in the Central Division is the language of the patent.

Court of Appeal

The language of proceedings in the Court of Appeal is the language used in the First Instance Division from which the appeal comes, subject to alternative agreement by the parties in which case an alternative language may be used, including the language of the patent.

Representation

Parties must be represented before the UPC: there is no possibility for individuals to appear in person.

Lawyers authorised to practice before a court of a contracting member state are able to represent parties before the UPC. However, in Suinno Mobile & AI Technologies Licensing Oy v Microsoft Corporation (UPC_CoA_563/2024), the Court of Appeal explained that in-house attorneys may act as representatives before the UPC. However, no corporate representative who has extensive administrative and financial powers within the party may serve as a representative of that party.

In addition, parties may be represented by European patent attorneys who have appropriate qualifications. These include the European Patent Litigation Certificate, awarded specifically for the UPC, as well as a number of other qualifications that enable a significant number of existing European patent attorneys to qualify as representatives.

UK based European patent attorneys are able to act as representatives before the UPC, there being no nationality or residence requirement to act as a representative.

The UPC is something of a hybrid, incorporating patent office or patent tribunal practices and approaches that are not seen in national courts. The judicial panel at First Instance in particular is likely always to include a technical judge (who will be a senior European patent attorney or former patent office tribunal member). Further, most of the procedure and briefing will be in writing, and the statements of case will require a substantial amount of technical content.

The UPC is a court of law. The legal judges will always of course also be the majority, whichever division is hearing the case. The procedure, rules (including jurisdiction), evidence, and remedy approaches are all aspects that come from court processes, and differ significantly from EPO or other patent office procedures.

Bearing all of that in mind, the best approach in anything other than the simplest case is likely to be to arrange representation that comprises a mixture of European patent attorneys and lawyers experienced in patent litigation. Indeed, this has been seen in many cases before the UPC.

Judges

There are two kinds of judge in the UPC: legal and technical. Legal judges are individuals eligible to sit as judges in their national courts, and are typically experienced national judges. They have experience and/or training in patent litigation.

Technical judges have a technical degree and demonstrable expertise in a particular field. They are typically senior European patent attorneys or former members of patent office tribunals.

In all proceedings, a judge-rapporteur is appointed from among the legal judges on the relevant panel. The judge-rapporteur manages the case, particularly in the interim procedure (as explained in the “Overview of Proceedings” section of this guide).

In the context of varying backgrounds of the UPC judges, it is crucial to consider tailoring submissions according to the nationalities of the judges on each panel and be mindful of the different approaches that may be required. It is also advisable to consider previous decisions and orders issued by the division in question.

Local and Regional Divisions

The Local and Regional Divisions generally sit in panels of three legally qualified judges. A technical judge may be added to the panel, and will be if invalidity is in issue. Most cases are therefore likely to have a technical judge.

Where there are panels of judges, they are international such that not all come from the same contracting member state (or, in the case of a Regional Division, not all come from the countries participating in that division). However, some Local Divisions may have a majority of ‘local’ judges – these are divisions in countries with a large average number of patent cases over a qualifying period. Thus the Local Divisions in at least Germany have a majority of local legal judges, as do a few others.

Central Division

The Central Division sits in a panel of two legal judges and one technical judge. The legal judges come from different contracting member states.

In any case at First Instance (Local, Regional or Central Divisions), the parties can agree to have a case heard by a single judge.

Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal sits in panels of five judges; three legal and two technical. The three legal judges come from different contracting member states.

| Local Division* | Regional Division* | Central Division* | Court of Appeal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of legal judges | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Technical judge? | Probably 1 | Probably 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Nationality of legal judges | Mixed but majority of "local" judges in some divisions | Mixed but majority from countries participating in the division | Mixed | Mixed |

*Possibility for case to be heard by a single judge.

Overview of proceedings

Substantive proceedings at First Instance

Substantive proceedings before the UPC comprise three stages: written, interim and oral procedures.

For a case at First Instance, an action is commenced by filing either a statement of claim or a statement for revocation, as appropriate. These must be quite detailed, and contain all the facts, evidence, argument and propositions of law relied upon. The UPC requires a “front-loaded” approach. Claims and documents must be filed (electronically) at the Registry of the UPC, which is responsible for service on defendants (and generally on the parties throughout the course of an action).

In biolitec Holding GmbH & Co KG v SIA LIGHTGUIDE International, Light Guide Optics Germany GmbH (UPC_CFI_714/2024) it was established that an action is considered as having been served on the actual date of access by the defendants to the UPC’s case management system (CMS), despite the defendants’ argument that a power of attorney to receive the claim had not yet been established on that date.

A defendant has three months to file their defence (and possible counterclaim), which must be similarly detailed. After this, there is an opportunity for subsequent rounds of written pleadings by both parties. These steps comprise the written procedure.

In some cases, such as when service of a statement of claim is made to parties located outside of Europe, or if there are a number of defendants to whom service is made at different times, deadlines for filings of defence and counterclaims may be extended, as was the case in Maxell, Ltd v Samsung Electronics (Co Ltd & Ors) (UPC_CFI_196/2025).

The UPC is prepared to issue a decision by default if the defendant does not take the opportunity to defend itself. It is therefore important that a defendant does not disregard a service of a statement of claim, and files a statement of defence within the three month deadline.

In air up group GmbH v Guangzhou Aiyun Yanwu Technology Co, Ltd (UPC_CFI_509/2023) it was stated that it must “always be possible to establish good service” even in a situation where no reply was received from the local competent authority to a status request for service of an application for a preliminary injunction. Accordingly, a decision by default was issued, and publication of the decision on the UPC’s website was considered to constitute good service of the decision.

Once the written procedure closes, the next stage is the interim procedure. During this stage, the judge-rapporteur makes a number of directions in order to prepare for the oral procedure (see below). This may include the parties attending an interim conference. This part of the action is to provide clarification on certain points, produce further evidence and consider the roles of experts and/or experiments. The interim procedure should be completed within three months of the end of the written procedure.

Once the interim procedure is completed, the action moves on to the oral procedure. The judge-rapporteur summons the parties to an oral hearing about two months after the close of the interim procedure. The UPC will endeavour to limit the duration of the oral hearing to one day although it could be longer in appropriate cases. The oral hearing includes the oral submissions of the parties together with the examination of any experts or witnesses, although there may be a separate witness hearing in addition.

The written judgment should be provided within six weeks of the hearing. It is also intended that First Instance proceedings should be concluded within no more than about a year from commencement.

At any stage of the procedure, the UPC may propose that the parties liaise with the Mediation and Arbitration Centre (or any other appropriate alternative dispute resolution service or process) in order to explore the possibility of settlement. This is most likely to be recommended by the judge-rapporteur during the interim procedure.

Interim proceedings

Parties may apply for interim orders and remedies at various stages of the case, or indeed before an action commences (for example, to obtain an asset freezing order or evidence preservation order). These proceedings typically follow a written and oral procedure, and in appropriate cases an oral hearing.

Appeal proceedings

Appeals may be brought against both procedural and substantive decisions of any First Instance division of the UPC. Procedural appeals are frequent, and important, in order that a harmonised procedure is encouraged in all Local and Regional Divisions. Appeals can also be brought against damages and costs decisions.

There are also three stages in appeal proceedings: written, interim and oral. They are broadly similar to those in First Instance proceedings (with much shortened timescales for procedural appeals).

Damages proceedings

A successful claimant is entitled to commence an application to determine damages (and possibly seek an interim award of damages). Such an application, if contested by the unsuccessful defendant, follows a similar three stage approach to that in First Instance substantive proceedings but with such reduced timetable as the judge-rapporteur may order.

Proceedings for recovery of costs

A successful party may commence a proceeding for the recovery of costs by filing an application which includes the necessary particulars of costs incurred. If contested by the unsuccessful party, that party has the opportunity to comment in writing on the costs requested. The judge-rapporteur decides on the costs to be awarded, in writing.

Stay of proceedings

The UPC may stay proceedings under exceptional circumstances, where:

- The relevant patent is also the subject of opposition or limitation proceedings before the EPO;

- The relevant SPC is also the subject of national proceedings; or

- An appeal is brought against a decision or order of the Court of First Instance.

However, the Munich Local Division explained in Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril (Gmbh & Life Sciences Pvt Ltd) (UPC_CFI_15/2023) that there is no obligation to stay the proceedings in such situations, and refused to stay infringement proceedings, pending an appeal of the Paris Central Division’s finding on validity of the patent in question. The Munich Local Division also made clear that the decision to stay proceedings should be made on a case-by-case basis (see the “Relationship with opposition and appeal proceedings at the EPO” section below).

Transparency of proceedings

While orders and decisions of the UPC are publically available on its website, written pleadings and evidence filed during proceedings are not automatically made public. Instead, third parties wishing to gain access to written pleadings and evidence are required to make a “reasoned request” to the court. A decision on whether to provide the requested documents is also only issued after consulting the parties involved in the proceedings.

The appropriate standard to be applied when considering requests by third parties for access to written pleadings and evidence was considered by the Court of Appeal in Ocado Innovation Limited v Autostore (Sp Zoo & Ors) (UPC_CoA_404/2023). The Court of Appeal held that the UPC register and proceedings held before the UPC should be open to the public, “unless the balance of interests is such that they are to be kept confidential”. The court consequently granted access to the statement of claim to an anonymous third party. This ruling by the Court of Appeal appears to set a generally permissive regime for access to pleadings and evidence at the UPC.

In Ocado Innovation Limited v Respondent (UPC_CoA_404/2023), the Court of Appeal also ruled that a member of the public requesting access to documents must be represented by a professional representative.

Furthermore, the UPC Courts of First Instance have held there to be no legal basis for costs to be awarded following a request for access to written pleadings and evidence, in Meril (Italy srl & Ors) v SWAT Medical AB (UPC_CFI_189/2024), and Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril Life Sciences (Pvt Limited & Ors) (UPC_CFI_380/2023). These latter rulings provide welcome reassurance for third parties that they are unlikely to be held liable for costs of the parties to proceedings involved in responding to their request.

Remedies and defences

Interim remedies

A wide range of interim remedies are possible in the UPC, including:

- Interim (otherwise termed preliminary) injunctions.

- Preservation and obtaining of evidence (by inspection procedures similar to saisie-contrefaçon or production of documents similar to limited discovery).

- Asset freezing orders.

- Security for costs.

If a patentee does not act promptly then the preliminary measures are unlikely to be granted. In Valeo v Magna (UPC_CFI_347/2024) it was held that there is “no fixed deadline” by which a patentee must submit its application for provisional measure; the question is always whether the patentee’s conduct as a whole justified the conclusion that the enforcement of its rights is urgent or not.

The validity of the patent may also be considered in requests for preliminary measures. However, it has been held that it is the defendant’s responsibility to challenge the presumption of validity. In Hand Held Products Inc v Scandit AG (UPC_CFI_74/2024) the Munich Local Division held that the number of arguments raised against the validity must generally be reduced to the three best arguments from the perspective of the defendant.

Protective letters may be filed with the UPC at any time and allow a defendant to file evidence and arguments as to why they believe they do not infringe a patent under the jurisdiction of the UPC or reasons for invalidity of the patent. However, the decision to file a protective letter should be taken carefully. In myStromer AG v Revolt Zycling AG (UPC_CFI_177/2023) the defendant had filed a protective letter, but in doing so did not identify any prior art nor provide any detailed reasoning as to why the patent was not infringed. The Local Division held that the protective letter was not persuasive and granted an ex parte preliminary injunction on the same day.

The UPC may order security for costs if there is a risk that a party is unable to fulfil the costs order, or that the court may not be able to enforce the costs order. In NanoString Technologies Europe Limited v President and Fellows of Harvard College, security for costs was awarded based on concerns over NanoString having inadequate means to bear the legal costs and expenses incurred by Harvard. In contrast, in Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril Italy srl (UPC_CFI_255/2023), security for costs was not awarded, because the risk of any prospective costs order not being fulfilled by Meril Italy was deemed to be insignificant.

Final remedies

Following the substantive judgment, final remedies include:

- Damages or an account of profits (which are determined in a separate proceeding following trial and appeal, if not agreed).

- Interim award of damages pending full assessment.

- Injunctions (which are discretionary but likely to be widely granted – note there are no eBay-type rules on injunctions in the UPC).

- Destruction or delivery-up of infringing goods and/or materials or implements concerned.

- Recall from channels of commerce.

- Publication of judgment.

- If the patent is revoked, an order for revocation.

- Costs recovery (see "UPC court fees and cost recovery" below).

FRAND

Defendants in some infringement proceedings before national courts have been able to avoid injunctions by arguing that they would have been willing to take a license for a standard essential patent (SEP) (if so offered by the patentee) on terms that are fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND). This is known as the FRAND defence, and (if successful) may be followed by FRAND licensing terms being set.

The first decision on an SEP was issued by the UPC in Koninklijke Philips NV v Belkin (GmbH & Ors) (UPC_CFI_390/2023) when a permanent injunction was ordered against Belkin in respect of the infringement of Philips’ patent. No FRAND disputes arose during this case.

In Panasonic Holdings Corporation v Guangdong OPPO Mobile Telecommunications Corp Ltd & OROPE Germany GmbH (UPC_CFI_210/2023), the Mannheim Local Division found that OPPO had infringed Panasonic’s patent. During the infringement proceedings, OPPO had raised a FRAND defence, but this (along with a counterclaim for determination of a FRAND rate) was dismissed.

UPC court fees and cost recovery

The UPC court fees and cost recovery rules should be taken into account at the commencement of any action in the UPC, and when taking any further step in proceedings. The fees are relatively substantial and, because a losing party may be liable for the costs of the successful party, the costs and fee risk should be borne in mind. The position in the UPC is different from that in a number of national courts.

Court fees

Court fees in the UPC are a mixture of fixed and value-based fees.

All actions and interim applications in the UPC attract a fixed fee. For substantive proceedings, these range from around €3,000 for a damages proceeding, to €20,000 for a revocation proceeding. For interim applications, fixed fees range from €350 for inspection or preservation applications, to €11,000 for an application for an interim injunction.

In addition, certain substantive proceedings attract value-based fees, where the value of the proceeding exceeds €500,000. These value-based fees range from €2500 for cases exceeding €500,000 but less than €750,000, up to €325,000 for cases exceeding €50m in value.

Proceedings that incur a value-based fee include:

- Infringement actions.

- Infringement counterclaims.

- Actions for a declaration of non-infringement.

- Applications to determine damages.

Revocation actions and counterclaims for revocation do not attract a value-based fee. A revocation counterclaim will attract the same fee as the infringement action in which it is filed, up to a cap of €20,000 (which is the fixed fee for a revocation action).

There are fee reductions of around 40% for small and micro entities, as well as further reimbursements where a single judge hears the case or where the case is settled or withdrawn early.

Legal costs and fee recovery

Following a decision on the merits, the UPC operates a basic ‘loser pays’ principle. Article 69 of the UPC Agreement provides that reasonable and proportionate costs and other expenses of the successful party are borne by the unsuccessful party (unless fairness requires otherwise), up to certain limits.

The UPC Rules on Court Fees and Recoverable Costs provide for a scale of recoverable cost limits that apply to representation costs only (meaning legal representation). These limits are based on value and range from €38,000 for a case up to and including €250,000 in value, to €2m for cases exceeding €50m in value. These limits may be raised in exceptional cases, or lowered if an applicable cap may threaten the economic existence of a party.

Court fees should be recoverable in full, and third party costs (such as expert fees) are not capped, so are recoverable to the extent they have been necessarily and reasonably incurred.

Unreasonable or unnecessary costs are borne by the party which incurred them, regardless of outcome.

Relationship with opposition and appeal proceedings at the EPO

Opposition and any subsequent appeal proceedings at the EPO remain possible for conventional European patents and unitary patents. They can run in parallel with UPC proceedings.

Opposition at the EPO may be a popular option because it is cheaper than proceedings in the UPC. Opposition and appeal decisions also apply to conventional European patents validated in EPC states such as the UK, which is not a party to the UPC.

The UPC is nevertheless a further option for central invalidation proceedings, for the contracting member states, and one that is available throughout the life of the patent, not just the first nine months after grant.

Proceedings before the UPC are not stayed where there are opposition or limitation proceedings before the EPO, save where a decision in the opposition or other proceedings is expected to be given rapidly. In Meril Life Sciences PVT Limited & Ors v Edwards Lifesciences Corporation, the UPC Court of Appeal confirmed (in a series of relevant orders) that such decisions are not limited to final (EPO Board of Appeal) decisions; but the Regional Division ultimately refused to stay proceedings despite an imminent EPO Opposition Division decision (UPC_CFI_380/2023 and UPC_CoA_511/2024). This is different from the position before some national courts, where a stay may be likely if there is an opposition pending before the EPO.

The UPC’s approach to procedural matters has mostly been in line with EPO practice. For example, ,the Munich Central Division adopted a similar approach to the EPO in allowing late-filed auxiliary requests and documents into the proceedings in President and Fellows of Harvard College v NanoString Technologies Europe Limited (UPC_CFI_252/2023).

Similarly, the UPC’s approach to substantive matters has mostly been in line with EPO practice. The slight divergence from EPO practice is highlighted below.

Claim interpretation

In NanoString Technologies (Inc, Germany GmbH & Netherlands BV) v 10x Genomics Inc (UPC_CoA_335/2023), the UPC Court of Appeal set out the principles of claim interpretation that have been applied in subsequent first instance decisions at the UPC. In particular, the UPC Court of Appeal stated that the description and drawings must always be used as explanatory aids for interpretation, not just to resolve any ambiguities in the claim language, such that only after examination of the description and drawings does the scope of the claims become apparent.

No provision or legal test for infringement by equivalence is provided in the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA). However, in Plant-e BV & Plant-e Knowledge BV v Arkyne Technologies SL (UPC_CFI_239/2023), the Hague Local Division for the first time provided guidance on the doctrine of equivalents at the UPC. The court applied a test that was “based on the practice in various national jurisdictions” and found infringement by equivalence.

In Sodastream Industries Ltd v Aarke AB (UPC_CFI_373/2023), the Düsseldorf Local Division found that the defendant could not make use of a “Gillette defence” in the way it had been presented. The Gillette defence was also discussed in Plant-e BV & Plant-e Knowledge BV v Arkyne Technologies SL (UPC_CFI_239/2023), in which it was held that one of the questions which needs to be answered in order to find infringement via equivalence is whether there is a successful Gillette/Formstein defence.

Added matter

The UPC’s approach to added matter appears to be mostly in line with EPO practice.

For example, the UPC applied a very similar test to the EPO’s “gold standard” of direct and unambiguous disclosure in Abbott Diabetes Care Inc v Sibio Technology Limited & Umedwings Netherlands BV (UPC_CoA_382/2024), albeit in the context of the description as a whole.

This is contrasted with the UPC Court of Appeal considering for an assessment of intermediate generalisation, whether the feature missing from the claim would be deemed “necessary for achieving the overall aim and effect of the invention”. This is different from the consideration at the EPO of whether a “structural and functional relationship” exists between the features.

Intermediate generalisations were found to be unallowable in DexCom Inc v Abbott (Scandinavia Aktiebolag & Ors) (UPC_CFI_230/2023), for generalisation of a feature that was only disclosed for specific embodiments; and in Meril Italy srl v Edwards Lifesciences Corporation (UPC_CFI_15/2023 & UPC_CFI_255/2023), due to isolation of a non-optional feature that was originally disclosed only in combination with other features.

Sufficiency

There have been relatively few decisions from the UPC in relation to sufficiency of disclosure, but so far the UPC’s approach appears to be similar to the EPO’s approach.

For example, in FUJIFILM Corporation v Kodak Holding GmbH & Ors (UPC_CFI_355/2023), the Düsseldorf Local Division held that the patent “does not disclose the claimed invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by a person skilled in the art over the complete scope of the granted claims”, and therefore the patent was revoked.

Novelty

The UPC’s approach to novelty appears to be in line with EPO practice.

For example, in NanoString Technologies Europe Limited v President and Fellows of Harvard College (UPC_CFI_252/2023), the Munich Central Division confirmed that what is decisive for novelty is whether the subject-matter of the claim with all its features, is directly and unambiguously disclosed in the prior art citation.

Also, in Sanofi Biotechnologies SAS & Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc v Amgen Inc & Ors (UPC_CFI_505/2024), the Düsseldorf Local Division confirmed that second medical use claims are purpose-limited; and patentable, provided the specific use is novel (and inventive).

Inventive step

The UPC’s approach to inventive step has been mixed and in some decisions, there has been some slight divergence from EPO practice.

In NanoString Technologies v President and Fellows of Harvard College (UPC_CoA_335/2023), the Court of Appeal neither endorsed nor criticised the EPO’s problem-solution approach, and did not acknowledge use of any particular methodology. In effect, the Court of Appeal left open the possibility of assessing inventive step using the problem-solution approach or a national approach, or establishing its own approach.

In Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH & Ors v Amgen Inc (UPC_CFI_1/2023), the Munich Central Division decided that inventive step is to be assessed from any “realistic” starting point, and that there can be several realistic starting points. On that basis, Amgen’s arguments that another document was “closer” and “more realistic” were not successful. In addition, the Munich Central Division decided that the skilled person may be a “team” of relevant technical persons; a claimed solution is obvious if the skilled person would be motivated to consider the claimed solution as a next step, without expecting any particular difficulties; and it may be allowed to combine multiple prior art disclosures. This is aligned with the German national approach to inventive step.

In line with this decision, in Meril (Italy Srl & Ors) v Edwards Lifesciences Corporation (UPC_CFI_255/2023), the Paris Central Division did not follow the problem-solution approach for assessing the inventive step of the claims. However, the Paris Central Division still considered the problem encountered by the skilled person (again, a team), and whether the cited documents provided motivation to make the required modifications.

In NJOY v Juul (UPC_CFI_315/2023), the Paris Central carefully considered what should be taken as the underlying problem and held that what is decisive is whether what is claimed as an invention did or did not follow from the prior art in such a way that the skilled person would have found it in their attempt to solve the underlying problem on the basis of their knowledge and skills.

More recently the Munich Local Division has adopted the EPO’s problem-solution approach in Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril Gmbh & Ors (UPC_CFI_501/2023), with an explanation that this is to align EPO and UPC practice. In particular, the Munich Local Division said that the problem-solution approach shall be applied (to the extent feasible) for assessing obviousness of a claimed invention, “to enhance legal certainty and further align the jurisprudence of the Unified Patent Court with the jurisprudence of the European Patent Office and the Boards of Appeal”.

Whilst the case law on the assessment of inventive step develops, it is advisable to present any inventive step arguments bearing in mind the problem-solution approach of the EPO and the national approaches, particularly the German national approach. In practice this will involve developing full inventive step attacks or defences from any prior art document constituting a realistic starting point. The term “realistic” meaning “of interest” to the skilled person.