Agritech prototyping: the risk of public disclosure

To get a patent for any new device or process it must be novel, meaning that it has not already been made available to the public. Importantly, a thing may be made available to the public even if no-one actually sees it; a book on a library shelf is clearly available to the public whether someone reads it or not. Therefore this is not a question of whether anyone actually sees and understands your invention, but merely whether they could have.

For agritech prototyping, often involving large equipment or field-scale processes, this is a pressing question when farms typically have multiple points of public access, either due to footpaths, nearby roads, farm shops, or a seasonal labour that are not direct employees.

Unlike for a library book, the question of whether testing a prototype device or process discloses an idea in a way that enables understanding is more nuanced, and has been tested several times in case law. In each case the key question has been what a member of the public is “free in equity and law” to glean from such activity.

To illustrate this, four court cases are briefly discussed below.

Manitowoc Beverage Systems: beer dispensing system

In the case of Manitowoc Beverage Systems Limited, BL O/019/14, a new system was developed for dispensing beer, which was cooled on the way to a dispensing font that was also cooled to create an ice effect. The system used a single glycol sub-zero coolant tank to the cool the beer and to ice the font.

This system was provided to several pubs for a short period of beta-testing before any patent application had been filed. Subsequently, after a patent was applied for and granted, Manitowoc sued a third party for infringement, which in turn claimed the patent was not valid as the system was made available to the public via these pubs. It was accepted there was no written evidence of a confidentiality agreement with the pubs, but notably the prototype cooler was provided inside a box that was riveted closed and security sealed.

Without opening the box it was not possible to understand how the system worked; meanwhile opening it would require damage to remove rivets and break the seal. It was therefore concluded that a reasonable person would understand that the box implied an obligation of confidentiality, and so the system in the box was not “made available to the public” despite being in public possession for some time.

Lux Traffic Controls: traffic light system

By contrast, in Lux Traffic, [1993] RPC 107 Ch D (Pat), in similar circumstances a new traffic light system was beta tested in field trials, with the new control system again in a locked box. This time however, the invention related to how the timing of the lights responded to traffic, and it was determined that a member of the public, just by observing the lights, could deduce the new behaviour produced by the control system. Therefore an enabling disclosure of the invention, if not the specific device implementing it, was made available to the public.

From this one can see that the issue is whether a member of the public can theoretically understand the invention in circumstances where there is no explicit or implicit obligation of confidentiality.

Emson: self-extending and retracting hose

Next, in the case of E Mishan & Sons Inc (trading as Emson) v Hozelock, [2019] EWHC 991 (Pat), the invention was for a self-extending and retracting hose that had a loose concertinaed outer tube of the extended length and an inner elastic tube of the retracted length, with the two layers only being attached at each end. When water was applied under pressure the elastic layer expanded to the full extended length and an increased diameter, but did not burst as it was constrained by the outer tube.

The inventor assembled a prototype of the hose in their garden, in view of the road, in September. They then tried the hose in their garden in November, before filing a patent application.

Again subsequently after a patent had been applied for and granted, Emson sued a third party for infringement which then claimed the patent was invalid due to public disclosure. In this case, it was accepted that the assembly process did not make clear that the goal was a variable length hose, and the later use did not reveal the internal assembly of the hose or exactly how it functioned: it would be necessary to be present on both occasions and to appreciate that they were the same item in both cases. Such a “mosaic” of disclosures was deemed inappropriate. However the judge noted that this decision relied on specifics of what could be understood on each individual day, and in different circumstances a skilled onlooker could have put two and two together. As such, the case did not create a general principle regarding mosaics that can be relied upon.

Interestingly however, in an obiter comment the judge noted that the inventor said he would be uncomfortable with someone watching him from the street and in this case would have packed up his materials and taken them into his house. The judge suggested that this made a difference; whilst if the public is given access to information then it is disclosed whether the public actually looks or not, it is quite another thing to say that information is available to the public if in fact no member of the public could have accessed it. If anyone trying to observe the inventor would not have seen anything because he would have packed everything up, then the situation is more like the locked box in Manitowoc; there is a deliberate censoring of information that is otherwise in the public sphere.

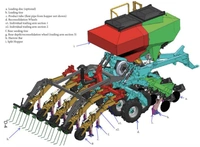

Claydon Yield-O-Meter: tractor-drawn seed-drill

The notion of active censorship during prototyping or trials was itself recently tested within an agricultural context, in the case of Claydon Yield-O-Meter v Mzuri Ltd, [2021] EWHC 1007 (IPEC).

Mr Claydon’s invention was a tractor-drawn seed-drill that minimised the disturbance of soil between sown rows of a crop, based on an exact alignment of cultivating tines in front of seeding tines. As with the cases already discussed, testing was carried out before filing a patent application, and in subsequent court action a potential infringer questioned whether the idea had been disclosed to the public.

Mr Claydon had previously “learned the hard way” that public prior disclosure of his invention would affect his ability to patent it, and so intended to prevent anyone who happened to be on a nearby public footpath from seeing any relevant details of the prototype, by using his vantage point in the tractor cab to move away before they got close.

As it turned out, there was never any member of the public present. However, the judge also noted that manoeuvring the tractor to prevent the public from seeing the prototype seed drill would have been much more difficult in practice than hiding a prototype garden hose in the circumstances of Emson. Separately, whilst not specifically discussed, it would also not be clear that a tractor turning in a field was imparting an air of confidentiality on a passerby. A skilled person would have had enough time to see that there were two tines, with the second set supplied by seed delivery tubes. Whilst it may have been harder to see or deduce exact alignment, they could have deduced that the tines must be aligned to the extent that the drill left in its wake strips of undisturbed soil between strips of disturbed soil. Notably the patent only claimed that “each of the tines in the second row is aligned with one of the tines in the first row whereby in use soil will only be disturbed in spaced apart linear regions”. Accordingly, the judge decided that: “Mr Claydon had to test his prototype, nobody saw any of the testing and I entirely understand why he believed that his invention was not publicly disclosed. Unfortunately for him, in law the prototype was made available to the public”.

Timing is everything

These four cases make clear that best practice is therefore to file a patent application before there is any risk of public disclosure. Actual witnesses are not necessary, and agritech prototypes are less likely to benefit from any of the small exemptions to the general principle of public disclosure discussed above.

If you have any questions about prototyping, disclosure, or patent applications, your D Young & Co advisor will be happy to help.

Case details at a glance

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: Patents Court

Parties: Lux Traffic Controls Limited v Pike Signals Limited

Date: 10 June 1993

Citation: [1993] RPC 107 Ch D (Pat)

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: UKIPO

Parties: Manitowoc Beverage Systems Limited & Messrs Scott

Date: 15 January 2014

Citation: BL O/019/14

Decision: dycip.com/ukipo-manitowoc

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: High Court of Justice Patents Court

Parties: E Mishan & Sons Inc trading as Emson v Hozelock Limited, Blue Gentian LLC and Telebrands Corp

Date: 17 April 2019

Citation: [2019] RPC 17, [2019] EWHC 991 (Pat)

Decision: dycip.com/emson-hozelock

Jurisdiction: England & Wales

Decision level: IPEC

Parties: Claydon Yield-O-Meter Limited v Mzuri Limited and Christopher Martin Cole

Date: 22 April 2021

Citation: [2021] EWHC 1007 (IPEC)

Decision: dycip.com/claydon-mzuri

Related articles

- Agritech innovation: how IP is cultivating the farms of the future, 16June 2025.

- The engine of precision farming: AI and agritech at the EPO, 19 June 2025.

- Agritech: farm use exemptions to patent infringement in the UK, 25 July 2025.

Related event

World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit, 22-23 September 2025. World Agri-Tech is a summit for those invested in advancing nature-positive, resilient agriculture and food systems. Doug Ealey will be attending.