Lush v Amazon - online retailers and sponsored links

The case of Cosmetic Warriors and Lush v Amazon has confirmed and clarified the recent cases of Google France, Interflora and L’Oreal v eBay regarding ‘double identity’ infringement in relation to the use of keywords and sponsored links, both within search engines (ie, Google’s AdWords service) and online retailing platforms (ie, Amazon).

This case, before the High Court in London, confirms that use of sponsored links for marketing purposes is still possible, however the content and use of such links must be carefully administered. Online retailers must therefore be cautious where a third party’s goods are not available for sale and yet that trade mark is still used to promote alternative goods.

When considering this case, it is important to remember that the claimants did not allow (or want) Lush products to be made available on the Amazon website. What was available were similar kinds of products from Lush’s competitors.

Legal background

In order to find ‘double identity’ infringement under Article 5(1)(a) Directive 2008/95/ EC (and the equivalent Article 9(1)(a) Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009), six conditions must be satisfied:

- there must be use of a sign by a third party within the relevant territory;

- the use must be in the course of trade;

- the use must be without the consent of the proprietor of the trade mark;

- the use must be of a sign which is identical to the trade mark;

- the use must be in relation to goods or services which are identical to those for which the trade mark is registered; and

- the use must be such as to affect or be liable to affect the functions of the trade mark.

In this case, it was clear that conditions (1), (3), (4) and (5) were fulfilled, due to the fact that Amazon was using a mark identical to Lush’s mark in relation to identical goods by promoting alternative products. It therefore needed to be discussed whether criteria (2) and (6) were satisfied, in order for infringement to be established.

Damage to functions of a trade mark has been explored in Google France and Interflora Inc v Marks and Spencer plc, the latter case is currently on appeal.

Google France

The Google France case developed the test that if a consumer could not ascertain the origin of the goods, or could not do so ‘without difficulty’, then the origin function of a trade mark had been harmed.

Interflora v Marks and Spencer

In relation to the investment function, the Interflora case held that if keyword advertising adversely affects the reputation of the trade mark, then there is damage.

Google AdWords

As part of its marketing strategy, Amazon had obtained “lush” as a Google AdWord, which resulted in ‘sponsored ads’ appearing at the top of the Google search results page. It is clear from the Google France decision that such use of a third party mark by the advertiser is deemed to be ‘in the course of trade’, and therefore fulfils condition (2) above. It is to be remembered, however, that Google itself does not infringe third party rights by selling a keyword containing a third party’s mark, so long as Google remains passive in simply offering keywords for sale.

In the present case, the first type of sponsored advertisement included the wording “Lush Soap at Amazon.co.uk”. John Baldwin QC, sitting as a deputy judge of the High Court, noted that as the sponsored advertisement specifically mentioned “Lush” within it, consumers would assume that genuine Lush goods were on offer. This was particularly so due to Amazon’s reputation in offering a wide range of products for sale from different companies. Therefore, as consumers would not be able to tell without difficulty that the goods referred to in the ad were not genuine Lush products, criteria (6) above was also satisfied. The ‘without difficulty’ test, established in the Google France case, was discussed. Whilst the notion may allow for some ‘simple enquiry’ to be made before being deemed too ‘difficult’, the deputy judge thought that a consumer would persevere somewhat to attempt to find genuine goods, due to the appearance of “Lush” in the wording of the sponsored advertisement.

The second type of sponsored advertisement at issue did not mention “Lush”, only the phrase “Large Range of Bath Bombs”. It was noted that whilst “bath bomb” was once uniquely associated with Lush, the term became generic around twenty years ago. The deputy judge was keen to point out that he believed the average consumer was aware of the concept of sponsored advertisements and had a basic understanding of how they aimed to promote competitor products. Therefore, the second variation of the sponsored advertisement was permissible; the consumer would understand this was not an advert for genuine Lush products.

This would suggest that it is sensible not to include a third party trade mark within the text of a sponsored advertisement for an alternative product. However, it is important to recall that in Interflora, there was liability even though the Marks and Spencer (M&S) sponsored advertisement (which appeared when searching the term “Interflora”) did not specifically mention Interflora within it. This was probably due to the somewhat unique nature of Interflora’s network of independent florists, from which a consumer may well think that the M&S and Interflora were commercially connected.

Amazon search facility

Significantly, this case relates to when the retailer, here Amazon, does not sell the actual products of the trade mark owner, but is using a third party trade mark to promote alternative products – in this case via Amazon’s internal search engine for its website.

The deputy judge began by stating that Amazon would not be liable where third party sellers were using the “Lush” trade mark on their goods and were using the Amazon website merely as an online marketplace, as held in L’Oreal v eBay. However, in this case, Amazon both operated the search facility and provided three categories of services to customers, being:

a) goods sold and supplied by Amazon;

b) supplying goods owned by a third party where Amazon provides fulfilment services (a range of services such as stocking, dispatching the order, customer service and returns); and

c) facilitating the sale of goods which are owned, sold and supplied by a third party.

Firstly, it was noted by the deputy judge that Amazon could not claim that its two roles in operating the Amazon search facility and commercially selling (or assisting to sell) products could not be held as distinct, as ultimately the search engine facility functioned to promote sales of such goods.

Secondly, he stated that he did not need to distinguish between the three categories of services above for the purpose of determining liability, as whilst Amazon is just an online marketplace for category (c), such services were closely connected with the other two categories, in both of which there was enough of a commercial communication by Amazon in order to constitute use ‘in the course of trade’ (ie, to satisfy (2) above).

What ‘uses’ infringe?

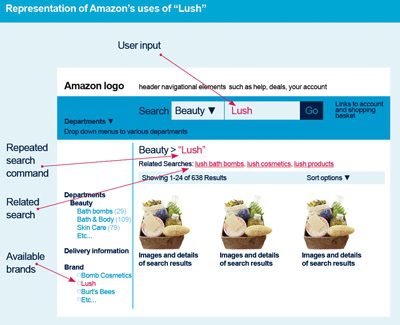

A number of different uses of “Lush” by Amazon were complained of: user input, autocomplete function, repeat of search command, related search results and available brand list.

User input

As this concerned the consumer typing the word, this was held not to constitute infringement by Amazon.

Autocomplete function

This use relates to the suggested text in a drop down menu when the consumer inputs letters into the search bar. In this case, when the consumer typed “Lu”, the Amazon search facility autocompleted the results to include “Lush” in a drop down menu for selection by the user. It was held that this did constitute use in the course of trade (criteria (2)) as Amazon had thereby made a commercial communication that it was selling the goods on the website.

In relation to damaging the origin function of the Lush trade mark, as there was no overt indication whatsoever that Lush products are not available for purchase on the Amazon website, and as the consumer has effectively been informed (from the drop down menu) that Lush products are available, it was held that the average consumer would not be able to ascertain without difficulty that the goods to which they were subsequently directed did not originate from Lush.

The advertising function was also held to be harmed, due to the fact that Amazon was using the ‘quality of attracting custom’ of Lush to attract the attention of customers and divert sales to third party goods.

In relation to the investment function, Lush successfully argued that its reputation had been damaged as it was a well respected ethical company which had decided not to be sold via Amazon.

Repeated search command and related search results

Whilst it was accepted that the repeat of “Lush” under the search bar resulted from Amazon’s standard algorithm, it was still deemed to be use in the course of trade, due to the inseparability of Amazon’s role as a search engine and commercial business. The same principle was held regarding the related search results.

It was also held that such uses were damaging to the origin, advertising and investment functions of the LUSH trade mark, for the reasons described above.

Available brands

Whilst the Lush brand of the claimants was not available on Amazon, there was in fact a separate brand called Lush stocked by Amazon which sold hair extensions. For that reason, this claim of infringement was rejected.

Future application

As technologies advance, so must the law. It is accepted that those who draft legislation will always be playing catch up, as well as trying to predict the next developments. For that reason it rests with the courts to make decisions that attempt to control and develop this legal sphere.

It will be interesting to see the impact of this judgment, and whether it will be curtailed by the fact that it was decided by a deputy judge.

We can see the potential for this decision to have quite wide-reaching effect, for example in relation to online marketplaces that sell counterfeit goods and how online marketplaces provide user friendly search facilities.

In relation to the finding that by providing fulfilment services to a third party Amazon is “using [the trade mark] in the course of trade”, we will also see what impact this may have on the implementation of the E-Commerce Directive 2000/31/EC and the ‘hosting defence’ – an area of law that remains uncertain.

Useful links

- England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decision on Cosmetic Warriors Ltd & Anor v amazon.co.uk Ltd & Anor [2014] EWHC 181 (Ch) (10 February 2014).

- Joined Cases C-236/08 to C-238/08 Google France SARL and Google Inc v Louis Vuitton Malletier SA and Others.

- Interflora Inc and Interflora British Unit v Marks & Spencer plc and Flowers Direct Online Ltd judgment.

- L’Oréal SA and Others v eBay International AG and Others.